Appearance

A Guide to the Faithful Texture Database

The Faithful texture database powers the submission system, texture gallery, and CompliBot texture lookup. It tracks every unique image file used in all reasonably modern Minecraft versions (>=1.4.6, b1.7.3, and Bedrock Edition), along with their distinct uses, file paths, and versions.

This guide doesn't go into extensive detail as to what every texture-related Faithful API endpoint does, but rather aims to provide a high-level overview of how everything functions and links together at a broad scope. This should be reasonably comfortable for non-developers to read, but some basic knowledge about database management will go a long way.

TIP

All Faithful API endpoints under /v2/textures, /v2/uses, and /v2/paths, and most of the /v2/gallery and /v2/versions endpoints are handled by this portion of the database.

Overview

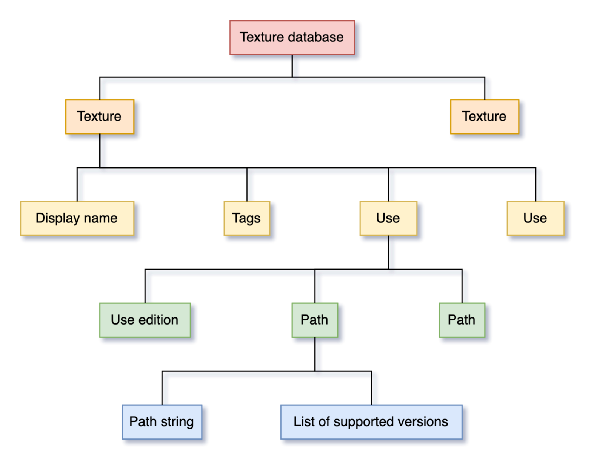

Note: Two of the same thing on a level means there can be multiple of them.

Note: Two of the same thing on a level means there can be multiple of them.The Faithful texture database is organized into three main collection tables: textures, uses, and paths. While they may appear to be one unified collection in practice, they are actually stored completely separately and are only linked together using IDs and keys at runtime. This enables lazy-loading collections when not all data is needed, and reduces the memory footprint of opening extremely large JSON files frequently.

Textures

ts

interface Texture {

/** Texture ID */

id: string;

/** Texture display name */

name: string;

/** Texture search tags */

tags: string[];

}

const example: Texture = {

id: "307",

name: "dirt",

tags: ["Java", "Bedrock", "Block"],

};Textures are the top-level entries of the texture database. Who would have thought?

Faithful defines a texture to be a unique image file in a given resource pack. This means that all identical image files in the game's assets across all game editions and versions have their file paths merged into a single texture entry.

This behavior is immensely useful across Faithful, both because the contribution system becomes much easier to maintain (a single contribution covers every possible place the same image is used) and a single texture submission can push to every location it exists automatically.

Texture IDs

Each texture is assigned a unique ID on creation, since Minecraft texture filenames aren't guaranteed to be unique (jungle.png is shared by unrelated villager, boat, and sign textures). Texture IDs are simple automatically-incrementing numeric values, so the first created texture has the ID #0, the second texture #1, etc.

Other texture-related collections like contributions use texture IDs to represent a relationship to a specific texture as a foreign key, so they're immutable to prevent data moving around. Additionally, if a texture gets removed or merged with another identical texture, the removed ID isn't ever reused for the same reason.

Note: it is unsafe to assume that every numeric ID less than the current maximum is a valid texture ID, since there may be "holes" where textures were deleted.

This is also why the latest texture ID is substantially greater than the actual number of textures indexed in the database.

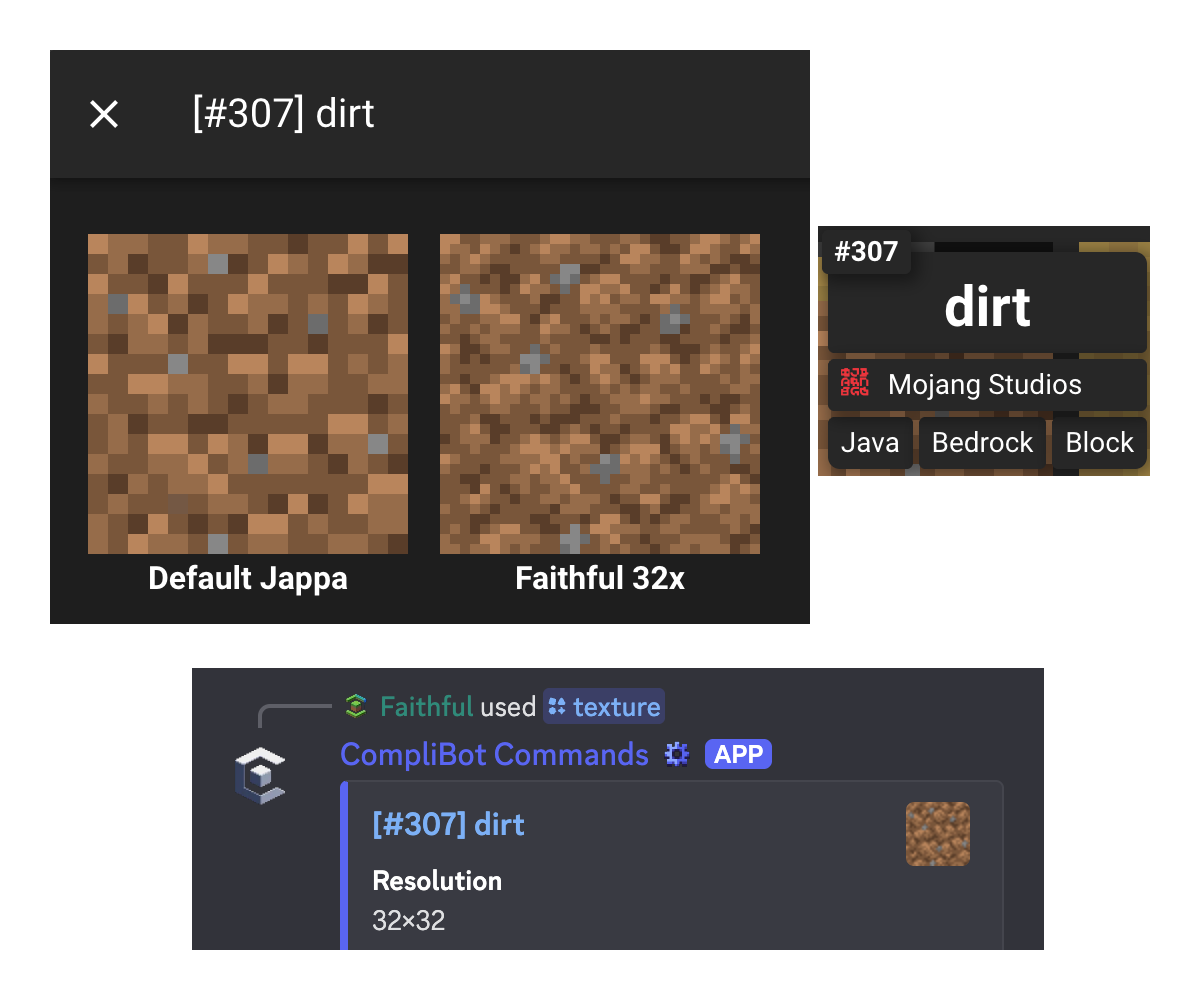

When interacting with the gallery or CompliBot, the texture ID is usually visible somewhere (in this case #307).

When interacting with the gallery or CompliBot, the texture ID is usually visible somewhere (in this case #307).Is there a pattern to how texture IDs are assigned?

Yes! The initial set of paths from when the Faithful texture database was created around 1.17 are alphabetically organized by folder (roughly IDs 0~2000).

Bedrock-exclusive textures from the same time period are listed after that, also alphabetically (roughly IDs 2000~5000).

Since then, textures have been added alongside game releases (with a few exceptions regarding legacy version support), so texture IDs are more-or-less chronological after 1.17 across both editions (IDs 5000+).

Additional Texture Information

A texture has two other top-level fields: its display name and its tags:

- The primary display name is mostly used for texture searching. If an image is used in multiple places with different names, the more obvious/common of the two is chosen for the display name (e.g.

glass_bottle.pngandpotion.pngshare a texture entry but the display name isglass_bottlesince the name is clearer and more obvious). - Texture tags are effectively a gallery search optimization that prevents unnecessarily searching path substrings when filtering results, since there are many more paths than textures. Tags are usually the folder directly after

textures/in the path with title casing, such asBlock,Item, orEntity.

Tag Ordering

By convention, tags are always listed in the order: Java, Realms, Bedrock, Java texture folder names, Bedrock-exclusive texture folder names.

Exemplar: Java, Bedrock, Block, GUI, UI.

Uses

ts

interface Use {

/** Use ID */

id: string;

/** Parent texture ID */

texture: number;

/** Use name */

name: string | null;

/** Use edition */

edition: string;

}

const example: Use = {

id: "307c",

texture: 307,

name: "options_backgroundd",

edition: "java",

};Uses define a specific "use" of a texture, i.e. distinct purposes of identical images (such as advancement backgrounds and their corresponding block textures). In most instances, they are only used to separate Java and Bedrock paths.

Use IDs are the texture ID with a lowercase character appended (e.g. texture 307's use IDs would be 307a, 307b, etc). This allows for some convenient optimizations, since you can slice off the final character of a use ID and always be guaranteed to have a valid texture ID.

By convention, the primary Java Edition use is placed first, since in many places only the first use is displayed or searched, and the Java names tend to be more intuitive due to the Flattening. Hence, you can be reasonably certain that the a use will be Java Edition and the b use Bedrock Edition if the texture is not exclusive to Bedrock Edition.

What if there are three uses?

In general, the Bedrock use will still take priority as the second use, with any additional uses being placed at the end.

While uses are not required to be named (nameless uses have a null name field), named uses only need to reflect the paths they store, and are hence able to be more precise than the texture display name. Returning to the glass_bottle example from earlier, the corresponding use names are potion and glass_bottle, which covers both distinct uses of the texture.

An example of uses and their order.

An example of uses and their order.Paths

ts

interface Path {

/** Path ID */

id: string;

/** Path parent use */

use: string;

/** Path string */

name: string;

/** Path versions */

versions: string[];

/** Whether the path has a corresponding MCMETA animation */

mcmeta: boolean;

}

const example: Path = {

id: "6948e70937fc5",

use: "307c",

name: "assets/minecraft/textures/gui/options_background.png",

versions: ["1.6.4", "1.7.10", "1.8.9", "1.9.4"]

mcmeta: false,

};Paths are the lowest level of the texture hierarchy, and define individual file paths where the texture file can be found, along with the specific versions they apply to.

Path IDs are pseudorandom hashes to better distinguish them from use and texture IDs. Since they are the final "link" in the chain, as nothing needs to reference path IDs, the actual value doesn't matter and isn't seen in user-facing UI anywhere. Paths link back to their parent use by storing its ID, and since a use ID is simply a texture ID with a letter appended, it is trivial to get a texture ID from a path entry by removing the final character.

Path names start from the pack folder name, which is usually assets/ for Java Edition and textures/ for Bedrock Edition. Only forward slashes are used, with none at the start, and the .png extension is always included for forward compatibility with potential non-png textures.

The MCMETA boolean specifically marks paths with a corresponding .mcmeta animation file. It is not stored on the texture level since not all paths are guaranteed to have an MCMETA file, such as Bedrock Edition paths, so by storing it on the path itself it's easy to search a texture's paths until a match is found.

Caveat with MCMETAs

Combined Bedrock Edition atlases, like some particle sheets, use the MCMETA toggle to denote that it's meant to be rendered as an animation, even though no MCMETA file actually exists. While this may appear to technically break the above rule, in reality there is no other place where an MCMETA file could be found, which is the reason why it needs to be stored on the path level normally.

This means that you cannot guarantee an MCMETA file existing when a path is marked as animated, and the fallback should be an empty property file:

json

{

"animation": {}

}Minecraft Version Storage

Minecraft versions mostly follow the conventions of the Minecraft launcher, with the latest patch version included (e.g. the database uses 1.17.1 instead of 1.17 even though both are functionally identical). However, there are a few special versions:

java-latestis guaranteed to point to the latest stable version of Minecraft.java-snapshotpoints to the latest snapshot of Minecraft, and goes unused when snapshots are not in development.bedrock-latestis the only Bedrock Edition version, since older versions are not officially supported.

When a new Minecraft version is made stable, the previous java-latest version is renamed to its final numbered version and java-snapshot is renamed to form the new java-latest version.

Summary

The Faithful texture database can effectively be summed up as follows:

- Textures are the root entry of the database, and are based on the number of unique image files in the game across all versions and editions.

- Uses divide a texture into its distinct purposes, but are most frequently used to split up paths by edition.

- Paths are linked to uses and store the actual filepaths, Minecraft versions it's used in, and animated textures.

Still have questions? Ask a developer on our Discord server for more information.